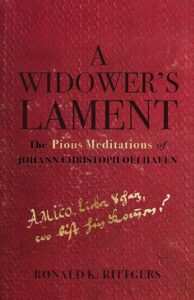

Sometimes what you say from the pulpit is not the same as what is heard in the pew. This disconnect also has the potential to blur our historical understanding: if the majority of the Reformation-era sources we study are written by pastors and professional theologians, we may not have all that precise of a grasp on what the average lay person thought and believed at the time. Ronald K. Rittgers, professor at Duke University, has attempted to fill this gap by publishing a translation of a remarkable work left by a Lutheran layman, Johann Christoph Oelhafen (1574-1631) of Nürnberg, which records his spiritual journey through grief at the loss of his beloved wife, Anna Maria, in 1619. Oelhafen provides us with a rare glimpse of how Lutheran preaching and teaching was heard, received, and put into practice by a Lutheran who was carrying a cross.

Sometimes what you say from the pulpit is not the same as what is heard in the pew. This disconnect also has the potential to blur our historical understanding: if the majority of the Reformation-era sources we study are written by pastors and professional theologians, we may not have all that precise of a grasp on what the average lay person thought and believed at the time. Ronald K. Rittgers, professor at Duke University, has attempted to fill this gap by publishing a translation of a remarkable work left by a Lutheran layman, Johann Christoph Oelhafen (1574-1631) of Nürnberg, which records his spiritual journey through grief at the loss of his beloved wife, Anna Maria, in 1619. Oelhafen provides us with a rare glimpse of how Lutheran preaching and teaching was heard, received, and put into practice by a Lutheran who was carrying a cross.

Rittgers provides an extensive introduction to Oelhafen’s work. He succinctly reviews the historical background of Nürnberg and its relation to the Lutheran Reformation, dwelling especially on its impact on the Oelhafen family and the ties Johann Christoph had to key theologians and pastors active in the city during his lifetime. He then proceeds to a brief overview of Oelhafen’s meditations. The majority of the introduction is devoted to situating the contents of Oelhafen’s work with respect to the work of modern scholarship on such topics as the role of emotions in early modernism and the like. Rittgers highlights a number of themes that he considers significant: the role of Oelhafen as the spiritual head in his home; his willingness to give expression to his grief in the face of a rising neo-Stoicism; Oelhafen’s appropriation of Lutheran means of consolation that, from the Reformation on, had taken the place of the Roman Catholic invocation of the saints and understanding of suffering as expiatory and purgative (and therefore thought to shorten the duration one would need to spend in purgatory). But Rittgers considers the most valuable contribution modern scholarship can expect to gain from Oelhafen’s work to be as an example of Lutheran lament, deeply rooted in the Gospel and the means of grace, informed by vocational self-understanding and the theology of the cross. In closing his introduction, Rittgers acknowledges that Oelhafen himself never intended for the work to be published, writing it primarily as addressed to God (and also himself and, doubtless, his children and posterity).

Following his extensive introduction, Rittgers publishes the translation of Oelhafen’s work, consisting of 77 entries. The entries consist of prose reflections, prayers, popular hymns, devotional writings or hymns slightly modified by Oelhafen, as well as some original hymns and poems that he composed. Oelhafen dated each entry, writing the majority of them on Sundays and noting the Sunday of the church year together with the calendar date.

One of the most intriguing aspects of Oelhafen’s meditations is the way that the lectionary and liturgy shaped his piety. Many of his entries reflect what Oelhafen would have heard in church that morning, suggesting that his Sunday afternoons included time spent in reflection on the church year, the sermon, and application to his own situation as a grieving husband. If one is looking for evidence of the formative value afforded by Lutheran worship, it can be found here. Oelhafen’s personal devotional life grew out of the worship life he enjoyed in his congregation.

The manner in which Oelhafen grieved the loss of his beloved wife also gives evidence of a number of distinctively Lutheran theological emphases. Oelhafen treasured the means of grace, and one of the most impressive sections of his work deals with his preparation for receiving the Lord’s Supper on Green (Maundy) Thursday. Oelhafen details how he prepared to go to private confession, made confession of his sins, and received absolution from the pastor prior to receiving the sacrament. It is clear that, in the midst of his grief at the loss of his wife, Holy Week in 1619 was for Oelhafen a particular moment in which the ministry of Word and Sacrament made all the difference in the world.

Another Lutheran distinctive is Oelhafen’s vocational self-understanding. He bemoans the fate of his eight surviving children in losing a dear mother and implores the Lord to help him carry out his role as their father. A number of entries towards the middle of his work are written while Oelhafen was traveling on official business for the city of Nürnberg and relate his concerns for the temporal well-being and defense of his beloved city. The Lutheran reforms that brought an end to the monasteries and ushered the spiritual life into the household clearly shaped Oelhafen’s life in profound ways.

Rittgers would suggest that Oelhafen’s lament, along with his willingness to give expression to his emotions, is most instructive. Especially in the early entries, shortly after the death of Anna Maria, Oelhafen mimics the lament language of the psalms, crying out to God and complaining that God has ripped his beloved away from him. And at various points later on, one will find Oelhafen insinuating that he is suicidal, that others have grown weary of his grief and expect that he should be at a point where he is no longer so distressed, and so on. Rittgers argues that this is, in fact, one of the ways in which Oelhafen was attempting to be a good father: by teaching his children how to cope with grief and loss in a godly manner. In our current age where suffering is avoided at all costs and we attempt to avoid the ugliness of death, the church could stand to learn how to lament.

Rittgers’s publication of The Pious Meditations will be of obvious value to scholars interested in the early seventeenth century. But I think that the work is also worthwhile for those who have an interest in better understanding the formative value of liturgy, lectionary, and hymnody, and how these can relate to and inform a lively devotional life in Christian homes. Likewise, Lutheran pastors who wish to learn more about lament might stand to gain from the example contained herein.